Nancy Wake was the Allies’ most decorated servicewoman of WWII, and the Gestapo’s most-wanted person. They code-named her ‘The White Mouse’ because of her ability to elude capture. When war broke out she was a young woman married to a wealthy Frenchman living a life of luxury in cosmopolitan Marseilles. She became a saboteur, organizer and Resistance fighter who led an army of 7,000 Maquis troops in guerrilla warfare to sabotage the Nazis. Her story is one of daring, courage and optimism in the face of impossible odds.

With a roar that makes both her name and nickname seem quaintly ironic this is Nancy at 89: “Somebody once asked me, ‘Have you ever been afraid?’ … Hah! I’ve never been afraid in my life.” The Sunday Times (South Africa) describes her as a real-life Charlotte Gray “whose exploits with the French Resistance make Sebastian Faulks’s fictional Charlotte Gray – read like an Enid Blyton girls’ school frolic.”

Nancy Wake, the White Mouse, 1943 Permission Nine Network, Australia.

Young Rebel

Nancy Wake was born on the gusty heights of Roseneath, Wellington, New Zealand, on 30 August 1912 to Charles Augustus and Ella Rosieur Wake. She was the youngest of six children. Her biography, Nancy Wake by Australian journalist and rugby personality Peter Fitzsimons, strongly records her edge lineage:

“Ella Rosieur Wake came from an interesting ethnic mix, her genetic pool bubbling with material from the Huguenots, the French Protestants who had famously fled France so they could pursue their religion freely, and Maori, as her English great-grandmother had been a Maori maiden by the name of Pourewa. She had been the first of her race to marry a white man, in the person of Nancy’s English great-grandfather Charles Cossell, and they were wed by the Reverend William Williams at Waimate Mission Station on 26 October, 1836. Legend has it that the great Maori chieftain, Hone Heke, had loved Pourewa himself and had sworn death to them both, but had been killed in the Maori Wars before fulfilling his threat. In sum, Ella’s people went a long, long way back in New Zealand, and physically she was like the land itself, rustically beautiful.

“Young Nancy’s father, Charles, however, was of solid English stock…an extremely good-looking, tall man of easy, extroverted charisma and enormous warmth. He was a journalist/editor by trade, then working on a Wellington newspaper. He was a dapper dresser who never seemed to have a worry in the world.”

When Nancy was 20-months-old, her parents moved to Sydney, where she grew up, chafing under the confines of genteel society. She was much younger than her brothers and sisters, and strongly independent. “I was a loner and I had a good imagination.” She was a rebel, in particular shunning her mother’s strict religious beliefs.

Wake was raised without affection by her embittered mother after her father had walked out on them. “I adored my father,” Wake recently told the Sunday Times, sitting on her bar stool with a walking stick in one hand and a gin and tonic in the other. “He was very good-looking. But he was a bastard. He went to New Zealand to make a movie about the Maoris, and he never came back. He sold our house from under us and we were kicked out.” Wake ran away from home at 16 and went to work as a nurse. Then an aunt in New Zealand sent her ?200 – a princely sum in those days. She left for the world. Wake used the money to travel to London and then to Europe where she worked as a journalist, swinging with a cosmopolitan set of independent and carefree young people. It was a glamorous life of parties and travel, and she lived it to the full. “I’ve always got on very well with the French, perhaps because I’m very natural.”

In 1930s Europe she witnessed the rise of Hitler, Nazism and anti-Semitism. In Vienna she saw horrific Dantescan scenes: Jews chained to massive wheels, rolled around the streets, and whipped by Nazi stormtroopers in a city square. The sight fed an early determination to work against the Nazis and eventually led to her courageous role in the French resistance.

In 1930s Europe she witnessed the rise of Hitler, Nazism and anti-Semitism. In Vienna she saw horrific Dantescan scenes: Jews chained to massive wheels, rolled around the streets, and whipped by Nazi stormtroopers in a city square. The sight fed an early determination to work against the Nazis and eventually led to her courageous role in the French resistance.

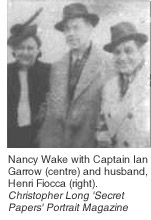

In 1939 Nancy married a handsome wealthy French industrialist, Henri Fiocca, in Marseilles (apparently seduced by his proficiency in tango). “He was the love of my life.” Together they had a charmed and sophisticated life of travel, dinner parties, champagne and caviar, residing in a luxury apartment on a hill overlooking Marseilles and its harbour.

Joining the Resistance

Six months after they married, Germany invaded France. Slowly but surely Nancy drew herself into the fight. In 1940 she crossed the line between observation and action, and joined the embryonic Resistance movement as a courier, smuggling messages and food to underground groups in Southern France. She bought an ambulance and used it to help refugees fleeing the German advance. Being the beautiful wife of a wealthy businessman, she had an ability to travel that few others could contemplate. She obtained false papers that allowed her to stay and work in the Vichy zone in occupied France, and became deeply involved in helping to spirit a thousand or more escaped prisoners of war and downed Allied fliers out of France through to Spain.

Nancy’s French Identity Card

Her missions with the Resistance meant her life was in constant danger. She became a suspect and was watched. The Gestapo tapped her phone and opened her mail. She took many identities and was so good at evading the Gestapo they nicknamed her the “White Mouse”. By 1943, Wake was No.1 on the Gestapo’s most wanted list and there was a five million-franc price on her head. It was too risky for Wake to stay in France and the Resistance decided she should go back to Britain.

“Henri said ‘You have to leave’, and I remember going out the door saying I’d do some shopping, that I’d be back soon. And I left and I never saw him again.”

Escape was not easy. She made six attempts to get out of France by crossing the Pyrenees into Spain. On one of these attempts she was captured by the French Milice (Vichy militia) in Toulouse and interrogated for four days. She held out, refusing to give the Milice any information, and with the help of the legendary ‘Scarlet Pimpernel of WWII’, Patrick O’Leary, tricked her captors into releasing her.

Finally, Wake got across the Pyrenees and from there to Britain. She was on safer ground, but had no news of her husband, who worked separately.

Back to the Fighting

Nancy Wake, then 31, became one of 39 women and 430 men in the French Section of the British Special Operations Executive which worked with local resistance groups to sabotage the Germans in the occupied territories. She was trained at a British Ministry of Defense camp in Scotland in survival skills, silent killing, codes and radio operation, night parachuting, plastic explosives, Sten guns, rifles, pistols and grenades. She and the other women recruited by the SOE were officially assigned to the First Aid Nursing Yeomantry and the true nature of their work remained a closely guarded secret until after the war.

Poster for the war office by Abram Games, “Your Talk May Kill Your Comrades”, 1942.

In late April 1944, Nancy Wake and another SOE operative, Major John Farmer, were parachuted into the Auvergne region in central France with orders to locate and organise the bands of Maquis, establish ammunition and arms caches from the nightly parachute drops, and arrange wireless communication with England. Their mission was to organise the Resistance in preparation for the D-Day invasion. The Resistance movement’s principal objective was to weaken the German army for a major attack by allied troops. Their targets were German installations, convoys and troops. When dropped over Auvergne Nancy’s parachute became stuck in a tree. Her agent said he hoped all trees could bear such beautiful fruit. Nancy told him not to give her ‘that French shit’.

There were 22,000 German troops in the area and initially 3-4,000 Maquis. Gaspard’s recruitment work, with the help of Wake, bolstered the numbers to 7,000. Nancy led these men in guerrilla warfare, inflicting severe damage on German troops and facilities. She collected and distributed weapons and ensured that her radio operatives maintained contact with the SOE in Britain. (See discussion point from a reader regarding the accuracy of these figures).

On one occasion Nancy cycled 500 km through several German checkpoints to replace codes her wireless operator had been forced to destroy in a German raid. Without these there would be no fresh orders or drops of weapons and supplies. Of all the amazing things she did during the war, Nancy believes this marathon ride was the most useful. She covered the distance in 71 hours, cycling through countryside and mountains almost non-stop. Her focus was rock steady to the end of her epic journey, when she wept in pain and relief.

“I got back and they said, “how are you?” I cried. I couldn’t stand up, I couldn’t sit down. I couldn’t do anything. I just cried.”

Pitched Battle

It was an extremely tough assignment: a near-sleepless life on the move, often hiding in the forests, travelling from group to group to train Maquis, motivate, plan and co-ordinate. She organised parachute drops that occurred four times a week to replenish arms and ammunition. There were numerous violent engagements with the Germans. The countryside was wracked with hostage taking, executions, burnings and reprisals.

No sector gave the Reich more cause for fury than Nancy’s – the Auvergne, the Fortress of France. Methodically the SS laid its plans and prepared to obliterate the group, whose stronghold was the plateau above Chaudes-Aiguwes. Troops were massed in towns all around the plateau, with artillery, mortars, aircraft and mobile guns. In June 1944 22,000 SS troops made their move on the 7,000 Maquis. Through bitter battle and then escape, Nancy and her army had cause to be satisfied: 1,400 German troops lay dead on the plateau, 100 of their own men.

Nancy continued her war: she personally led a raid on Gestapo headquarters in Montucon, and killed a sentry with her bare hands to keep him from alerting the guard during a raid on a German gun factory. She had to shoot her way out roadblocks; and execute a German female spy.

Victory and Sadness

On June 6, 1944, D-Day, allied troops began to force the German army out of France. On 25 August 1944, Paris was liberated and Wake led her troops into Vichy to celebrate. However her joy at the liberation of Paris was mixed with a tragedy she had secretly anticipated: in Vichy she learned that her beloved husband Henri was dead. A year after Nancy had left France in 1943, the Germans had captured Henri, tortured and executed him, because he refused to give them any information about the whereabouts of his wife.

On June 6, 1944, D-Day, allied troops began to force the German army out of France. On 25 August 1944, Paris was liberated and Wake led her troops into Vichy to celebrate. However her joy at the liberation of Paris was mixed with a tragedy she had secretly anticipated: in Vichy she learned that her beloved husband Henri was dead. A year after Nancy had left France in 1943, the Germans had captured Henri, tortured and executed him, because he refused to give them any information about the whereabouts of his wife.

Within a year Germany was defeated. 375 of the 469 SOE operatives in the French Section survived the war. Twelve of the 39 women operatives were killed by the Germans and three who returned had survived imprisonment and torture at Ravensbruck concentration camp. In all 600,000 French people were killed during World War II, 240,000 of them in prisons and concentration camps.

Post War

Nancy Wake continued to work with the SOE after the war, working at the British Air Ministry in the Intelligence Department. In 1960 she married a former prisoner of war, Englishman John Forward, and returned to Australia to live.

After the war her achievements were heralded by medals and awards: the George Medal from Britain for her leadership and bravery under fire, the Resistance Medal, Officer of the Legion d’Honneur and Croix de Guerre with two bronze palms and a silver star from France, and the Medal of Freedom from America.

However, for many years she was never awarded a medal by the Australian government. When the Australian Returned Services League recommended that Wake be awarded a medal, they were turned down. The Sydney Morning Herald (April 28th, 2000) surmised that she was turned down for a medal because she was born in New Zealand and was considered a New Zealand citizen. In 1994 she refused to donate her medals to the Museum of Australia and proclaimed to the New Zealand Press Association in Sydney (Evening Post, April 30, 1994) that she was still a New Zealander and reminded the press that she had kept her New Zealand passport, despite her 80 year absence from the country.

In 2004 Nancy Wake was, at long last, awarded the Companion of the Order of Australia. In 2006 Nancy received the NZ Returned Services Association’s highest honour, the RSA Badge in Gold, as well as life membership for her work with the French resistance during the war.

Recognition

Wake’s dramatic life story and her feisty, courageous personality made her the ideal subject for documentaries and dramatisations. She tells her own story with interviews, reconstructions, stills and film footage in the video Nancy Wake – Code Name: The White Mouse.

In 1987 a television mini-series was made about her life. However the subject was marred by historical liberties that were taken with her life story, such as showing her having an affair while working for the Resistance in Auvergne:

“What do you think my bosses in England would have thought, all those thousands of pounds to train me and for me to go and have an affair. Really!

“The mini-series was well-acted but in parts it was extremely stupid. At one stage they had me cooking eggs and bacon to feed the men. For goodness sake did the Allies parachute me into France to fry eggs and bacon for the men? There wasn’t an egg to be had for love nor money, and even if there had been why would I be frying it when I had men to do that sort of thing?”

Nancy Wake’s comrade Henri Tardivat perhaps best characterised the guerrilla chieftain:

“She is the most feminine woman I know, until the fighting starts. Then, she is like five men.”

On 6 December 2001, Nancy left her home in Port Macquarie, Australia for good to spend her final years in her cherished Europe.

“The people of Port Macquarie have been wonderful to me, as have most individual Australians I’ve met, but I just feel I would be better off in the UK or France where I could go to special occasions as a member of a services club.”

After making the final move back to England, Wake become a resident at the Stafford Hotel which had been a British and American forces club during the war. The hotel’s owners welcomed her warmly, absorbing most of the costs of her stay – helped occasionally by anonymous donations. Despite enjoying her residence at the hotel, Nancy Wake moved to the Star and Garter forces retirement home in 2003.

Nancy Wake passed away on 7 August 2011 at the retirement home where she had lived at the past eight years. Right up to her death, she remained assertive about what would happen to her body:

“I want to be cremated, and I want my ashes to be scattered over the mountains where I fought with the resistance. That will be good enough for me”.