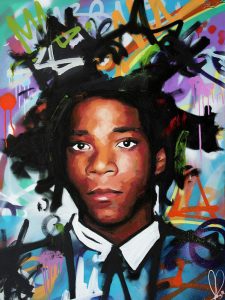

In the late 1970s, brief, cryptic messages began to appear on the  streets of Manhattan, all signed SAMO. These subversive, sometimes menacing statements, “Playing Art with Daddy’s Money,” “9 to 5 Clone,” and “Plush Safe…He Think,” piqued the curiosity of viewers around New York and soon gained notoriety in the art world. The works of SAMO, a tag calling up associations like “Sambo,” “Samson,” or “Same Old Shit,” eventually became known as the poetic defacements of Jean-Michel Basquiat, with partner Al Diaz.

streets of Manhattan, all signed SAMO. These subversive, sometimes menacing statements, “Playing Art with Daddy’s Money,” “9 to 5 Clone,” and “Plush Safe…He Think,” piqued the curiosity of viewers around New York and soon gained notoriety in the art world. The works of SAMO, a tag calling up associations like “Sambo,” “Samson,” or “Same Old Shit,” eventually became known as the poetic defacements of Jean-Michel Basquiat, with partner Al Diaz.

Born in Brooklyn to middle-class Haitian and Puerto Rican parents, Basquiat left home as a teenager to live in lower Manhattan, playing in a noise band, painting, and supporting himself with odd jobs. Around 1980, Basquiat’s work began to attract attention from the art world, particularly after a group of artists from the punk and graffiti underground held the Times Square Show in an abandoned massage parlor. A wall covered with the spray paint and brushwork of SAMO received favorable notices in the press and Basquiat started selling his paintings out of his tenement apartment.

Many of Basquiat’s paintings are in some way autobiographical and Untitled, 1981 is largely considered a form of self-portraiture. The skull here exists somewhere between life and death. The eyes are listless, the face is sunken in, and the head looks lobotomized and subdued. Yet, there are wild colors and spirited marks that suggest a surfeit of internal activity. Developing his own personal iconography, in this early work, Basquiat both alludes to modernist appropriation of African masks and employs the mask as a means of exploring identity. Basquiat labored over this painting for months—evident in the worked surface and imagery—while most of his pieces were completed with bursts of energy over a few days. Presented at his debut solo gallery exhibition in New York City, the intensity of the painting may also represent Basquiat’s anxieties surrounding the pressures of becoming a commercially successful artist.

Two famous men from the history of Jazz appear in Basquiat’s Horn Players, 1983: Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. In the upper left, Parker, whose nickname was “Bird,” holds his alto saxophone while Gillespie appears on the right with a trumpet. Basquiat’s painting is a tribute to jazz, specifically the bebop of Parker and Gillespie, and makes its tribute known by both rounding up the symbols and visual references of jazz while at the same deploying those references in a way as though to recreate music itself. The three panel work is full of repetition and visual punctuations. Art historian Robert Farris Thompson likens the multiple slashes of white paint across the surfaces to visual music, they “form their own beat, one, two, one-two-three. This is the clave beat, main artery of Afro-Cuban music.” Overall, the painting has the sense of rhythms emerging and then fading away, emerging again and recombining as though demonstrating the improvisation of jazz.

Basquiat used social commentary in his paintings as a tool for introspection and for identifying with his experiences in the black community of his time, as well as attacks on and systems of racism. Basquiat’s visual poetics were acutely political and direct in their criticism of colonialism and support for class struggle. He died of a heroin overdose at his art studio at the age of 27.

On May 18, 2017, at a Sotheby’s auction, a 1982 painting by Basquiat depicting a black skull with red and black rivulets (Untitled) set a new record high for any American artist at auction, selling for $110.5 million. Website